As Black History Month comes to an end, I wanted to share some of the research I’ve done on the music-related materials that black (or “colored”) libraries offered their patrons in the early 1900s.

According to a survey administered by a librarian at the New York Public Library in the early 1920s, areas in the southern and middle states that provided separate branches for black people were typically inferior and underfunded compared to those available to white citizens.

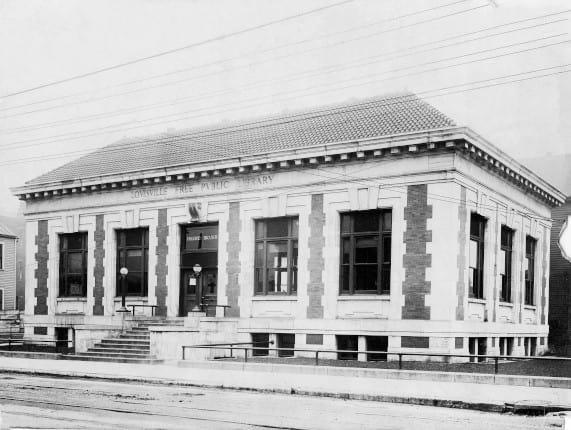

Additionally, white people often maintained administrative control of branches for black citizens; however, the Western Colored Branch in Louisville, Kentucky was an exception. It opened in 1905 and was the first free public library for Black readers. It was staffed and operated entirely by Black library workers. The Reverend Thomas F. Blue, a respected leader in the Louisville black community, was the head of the library. He established an apprentice program for aspiring library workers who then went on to work in libraries all throughout the south.

In the Kentucky Digital Library, I discovered “A List of Books Selected from Titles In the Western Colored Branch of the Louisville Free Public Library Recommended for First Purchase” that organized titles into Reference, Adult Non-Fiction, Adult Fiction, Juvenile Non-Fiction, and Juvenile Fiction. I examined the list for music-related titles and found 19. Some examples include Biographical Dictionary of Music by Theodore Baker, Masters of Music by Anna Chapin, One Hundred Folksongs by Granville Bantock, Folksongs of the American Negro by John Wesley Work, and Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings by Joel Harris.

Interestingly, the book on Uncle Remus is listed under Adult Non-Fiction and Juvenile Non-Fiction, but Uncle Remus was actually a fictional character created by Joel Harris, a white man, to share stories of life in the south. While the Uncle Remus stories were used to encourage tolerance and sympathy for Black people, they leaned into the harmful stereotype of the subservient black man who is content with his inferior position in American society.

As Cheryl Knott has explored in her book Not Free, Not For: All Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow, American libraries in the early-to-mid 1900s participated in the construction of blackness and whiteness. I believe there is so much more to uncover about the libraries that catered to the music ‑related information needs of black citizens during segregation.

For more information on the history of the Western Branch Library, check out this timeline created by the Louisville Free Public Library.

Comments are closed